Cache Coherency Series: Part 3 — False Sharing

Published:

Let’s review a bit what we covered in the previous part. We talked about

- How to formalize the cache coherence mechanism from part 1 by defining states, CPU operations, and bus transaction signals and using them to explain the mechanism.

- Pointing out how it is inefficient.

- How to optimize the mechanism by defining some more states and CPU operations and using them.

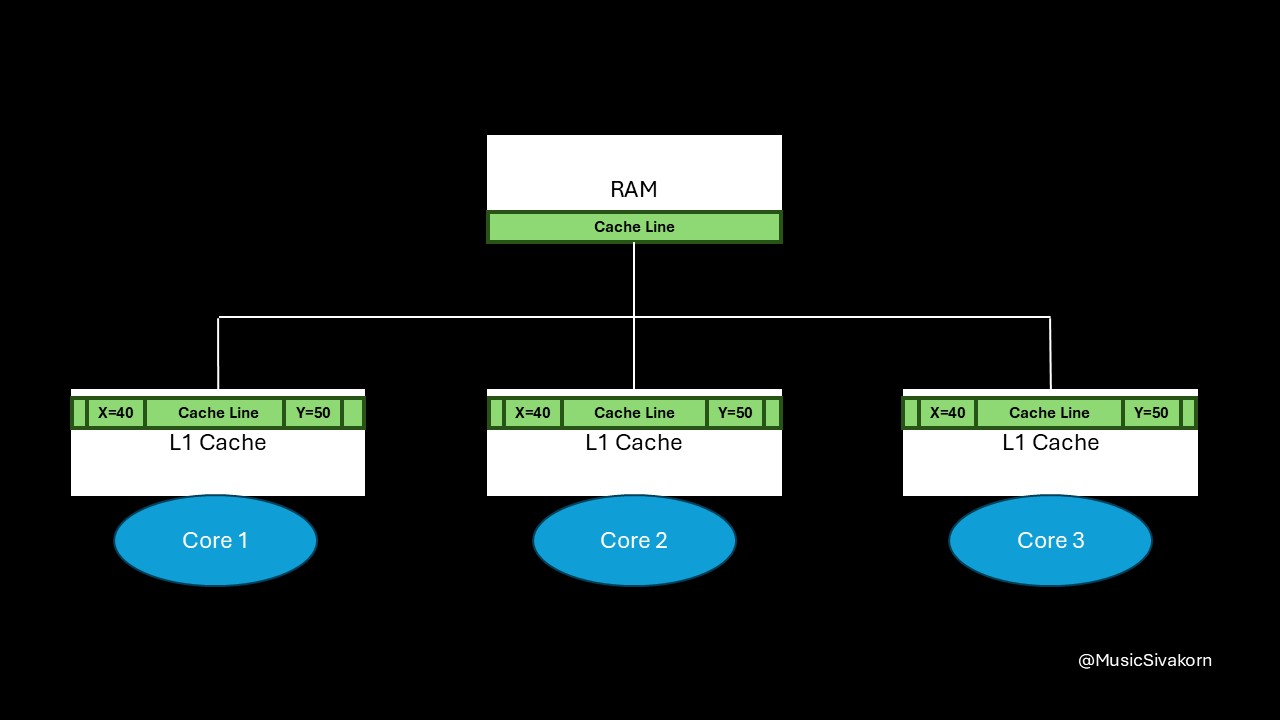

In the previous two parts, we focus on only one variable, which is a variable x, on a cache line. Now, we will focus on one more variable. Let it be a variable y.

We now focus on two variables on a cache line.

We now focus on two variables on a cache line.

For this part, we will not explain a mechanism in a formal way. So, if you still feel confused with a formal explanation in the part 2, don’t worry! We will use the more informal explanation style as used in the part 1. No states, CPU operations, and bus transaction signals will be used. However, understanding content in part 2 can help understand this topic better.

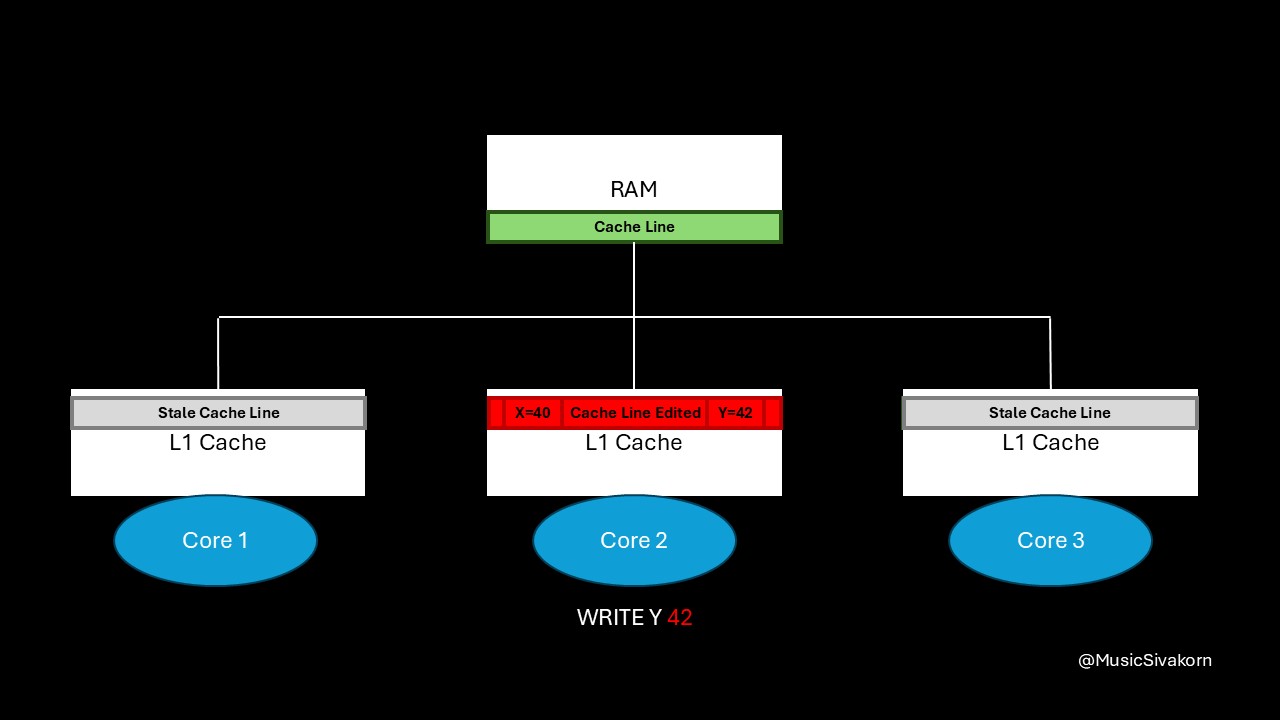

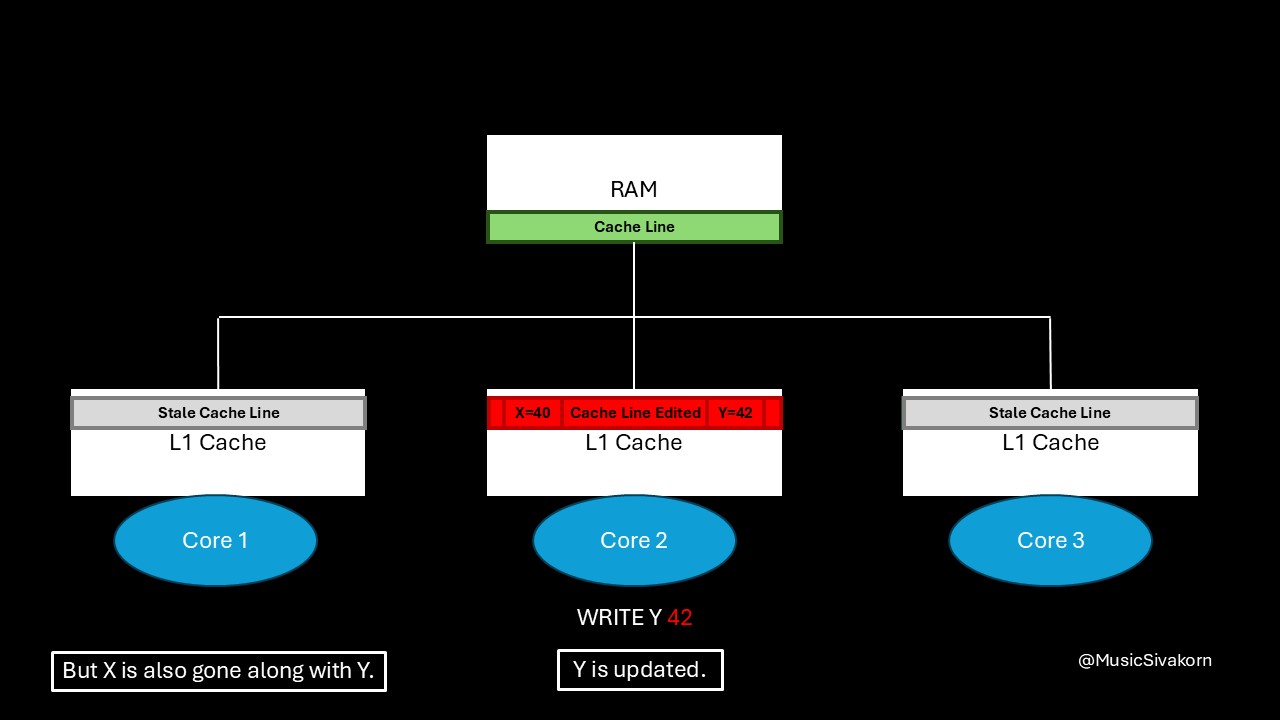

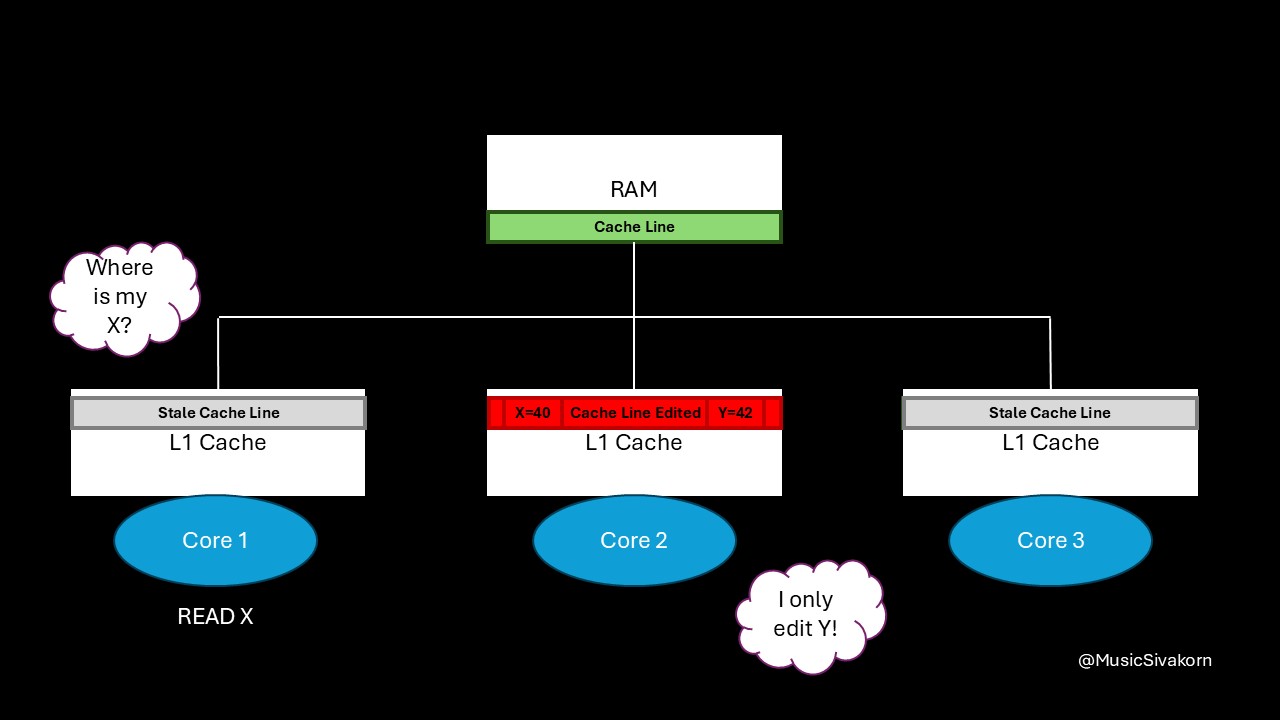

When the second core modifies the variable y to be 42, it broadcasts an invalidation signal to a bus, and the cache line in the first and third core becomes stale.

The second core modifies a variable y.

The second core modifies a variable y.

This part will assume that updated data will be written back to RAM first, and another core will fetch it from RAM.

When the first core wants to read the variable x, the second core has to update its updated cache line back to RAM first, and the first core then fetches this cache line to read the variable x.

Can you spot any inefficiency here?

The first core wants to read the variable x.

The first core wants to read the variable x.

The first and third core’s cache line become invalid when the variable y is modified; however, when the first core wants to read the variable x, a cache miss occurs because its cache line already becomes stale even if its desired variable (variable x) is not modified.

Instead of getting the data from its L1 cache, the first core has to wait for another core to write its modified cache line back to RAM before it can fetch it. This waiting is where most of the performance degradation comes from.

The cache line in the first core becomes stale. Both X and Y in the first core’s cache line are gone.

The cache line in the first core becomes stale. Both X and Y in the first core’s cache line are gone.

When the first core wants to read X, it must send a read request again even if the second core only modifies Y.

When the first core wants to read X, it must send a read request again even if the second core only modifies Y.

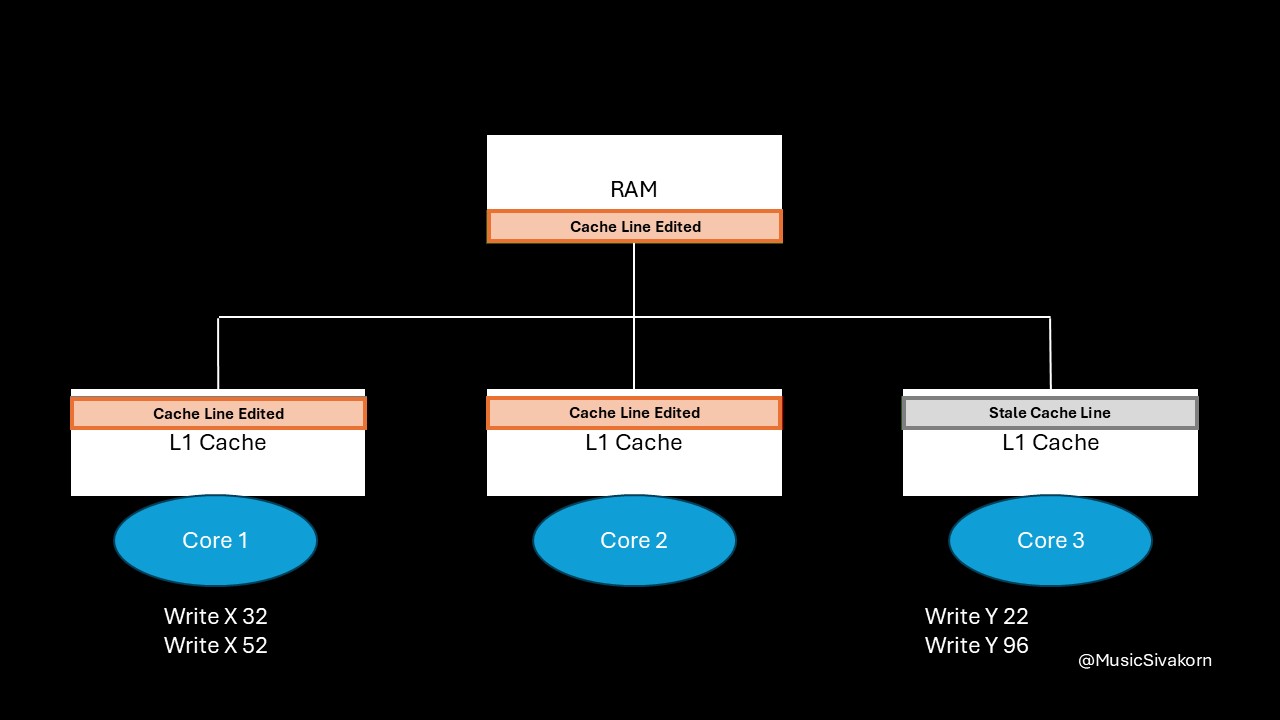

The problem can become more severe if each core does several modifications.

As an example, let the first and third core have two write operations each. We will assume that each core takes its turn to perform one write.

Multiple write operations on the first and third core.

Multiple write operations on the first and third core.

So, the operation sequence is as below.

---

config:

theme: 'forest'

---

graph LR

A(Write X 32) --> B(Write Y 22) --> C(Write X 52) --> D(Write Y 96)

As a reminder, both variable x and y are on the same cache line.

- The first core sends the

write signalto write 32 to x. Because it already has the most updated cache line from the previous read operation, it modifies its cache line and invalidates the second and third core’s cache line. - The third core sends the

write signalto write 22 to y. Because it has not had the most updated cache line yet, the first core writes the update back to RAM, and the third core fetches it to its cache. - The first core sends the

write signalto write 52 to x. Because it has not had the most updated cache line yet, the third core writes the update back to RAM, and the first core fetches it to its cache. - The third core sends the

write signalto write 96 to y. Because it has not had the most updated cache line yet, the first core writes the update back to RAM, and the third core fetches it to its cache.

How each operation affects the system in order.

How each operation affects the system in order.

This continuous invalidation and re-fetching of the entire cache line between cores is known as cache line bouncing or ping-ponging. A lot of latency is introduced even if two cores modify the different variable on the cache line. When the third core wants to modify the variable y, it must waste a lot of cycles to get the updated cache line that updates the unrelated variable x.

How to Solve this Problem?

To think about the solution of this problem, let’s think about the cause of this problem first. After that, think about the solution of your cause. Think about it!

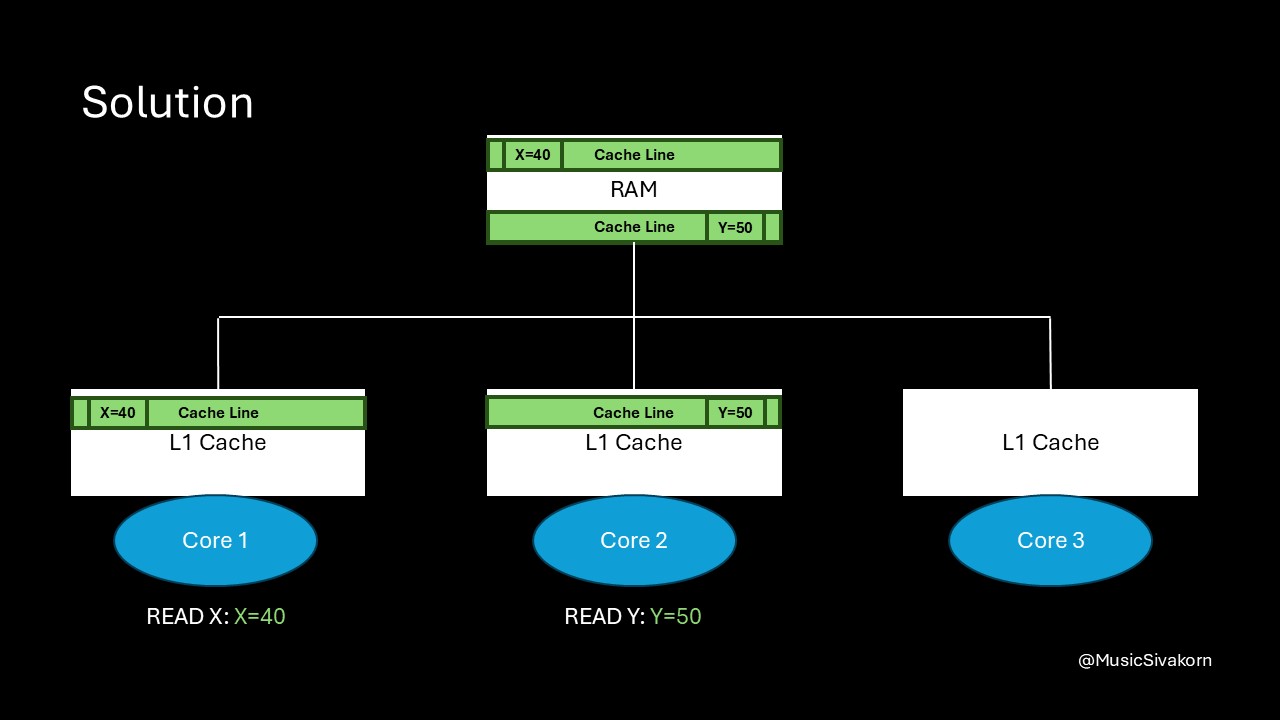

The cause of this problem is that both variables are stored on the same cache line. So, the solution is to separate them out to different cache lines.

Separate two different variables into two different cache lines.

Separate two different variables into two different cache lines.

When the first core reads the variable x, and the second core reads the variable y, they fetch the different cache line.

When the second core modifies y, the cache line in the first core is not invalidated because the second core now has the different cache line from the first cache. When the first core wants to read the variable x, the cache now hits!

When the second core modifies data, the first core’s CL is not invalidated. So, the cache hits when the first core reads data.

When the second core modifies data, the first core’s CL is not invalidated. So, the cache hits when the first core reads data.

The problem is solved! The first core does not need to unnecessarily fetch the unrelated updated cache line. As a result, if the variable x is not modified in another core, its cache line will not be invalidated because of modifying other variables anymore.

How to actually Implement this Solution?

This is one way to implement a cache line having two variables in C++.

struct Compact {

int x;

int y;

}

Compact myObj= {30, 40};

When myObj is allocated or accessed, both x and y are on the same cache line.

To separate the variable x and y from each other, we need an empty space to be placed between both variables. If that empty space is large enough, another variable will be compelled to be in another cache line. This technique is called padding.

Let assume that each int is 4 bytes, char is 1 byte, and cache line is 64 bytes. In our example, we can create an empty space having a size of 60 bytes between the variable x and y. As a result, the variable x will be only variable on one cache line, and the variable y will be pushed to be on another cache line.

struct Compact {

int x;

char padding[60];

int y;

}

Compact myObj= {30, 40};

How to implement a padding to avoid false sharing.

How to implement a padding to avoid false sharing.

As a result, this struct object does not suffer from the false sharing anymore when two cores modify the different variables.

How padding solves the false sharing problem.

How padding solves the false sharing problem.

Exercise

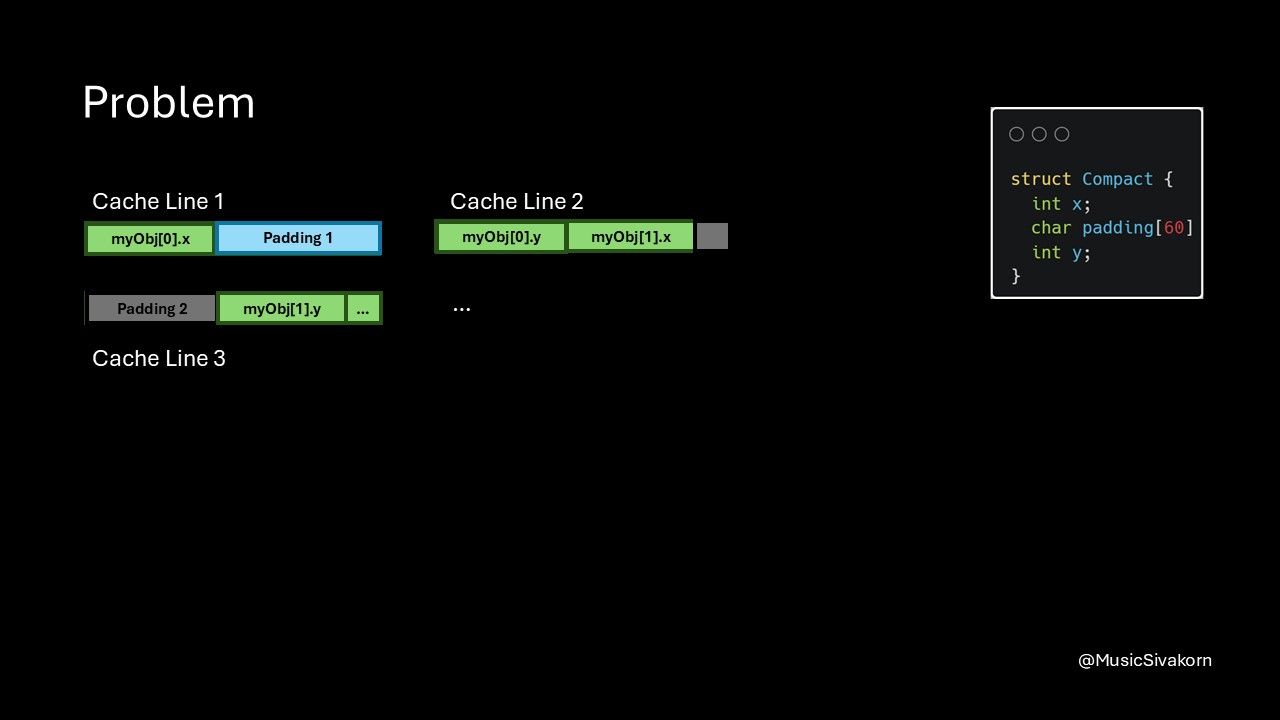

However, my padding still has a problem. What happen if I want to create an array of struct?

struct Compact {

int x;

char padding[60]

int y;

}

Compact myObj[10];

// ...

// Assume a set of operations to fill data to this array of struct

// ...

myObj[0].y and myObj[1].x are still on the same cache line! So, there is still a false sharing between different element of struct. For example, one core modifies myObj[0].y, and another core modifies myObj[1].x.

How can we solve this problem?

A problem of current padding method. There is still no padding between two elements of

A problem of current padding method. There is still no padding between two elements of myObj

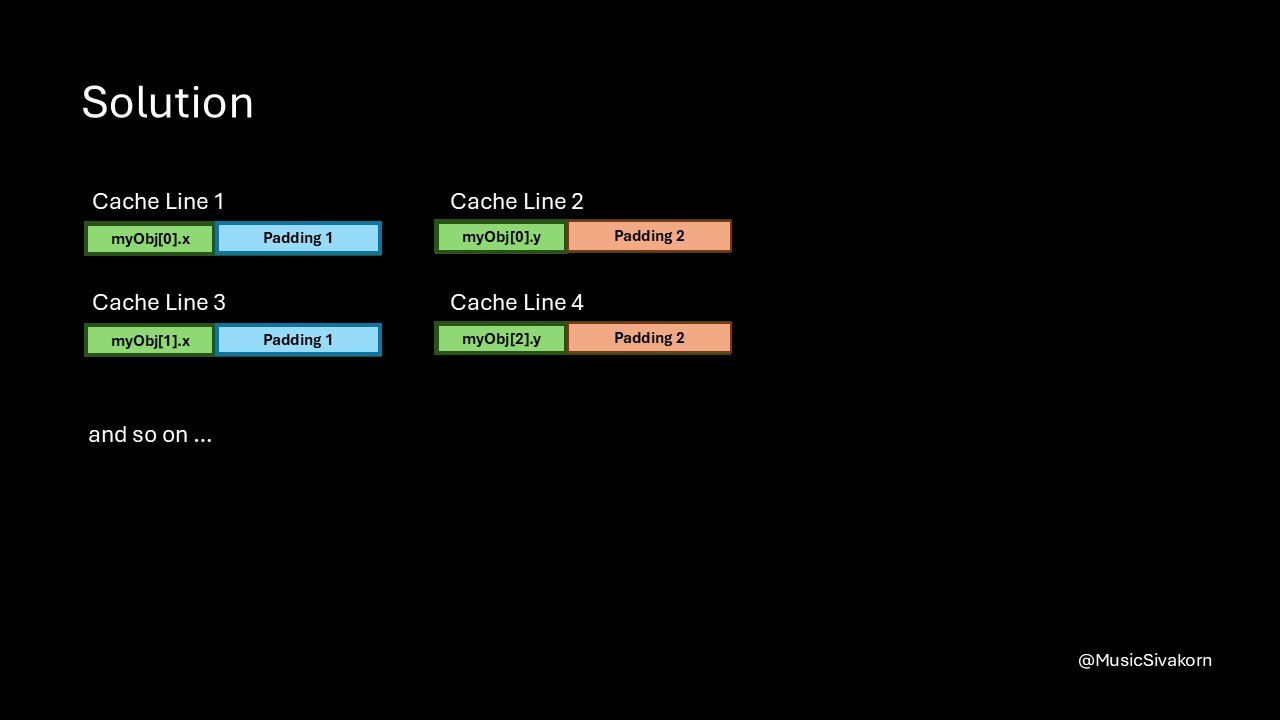

We can write a code to allocate a full cache line for each variable.

A new padding method

A new padding method

This is one possible way to implement the solution. I will treat how alignas(N) works to be out of scope of this part since I want to focus more on the concept.

struct Compact {

alignas(64) int x;

alignas(64) int y;

};

However, this solution comes with another problem as well. What is it?

We waste a lot of space to do a padding.

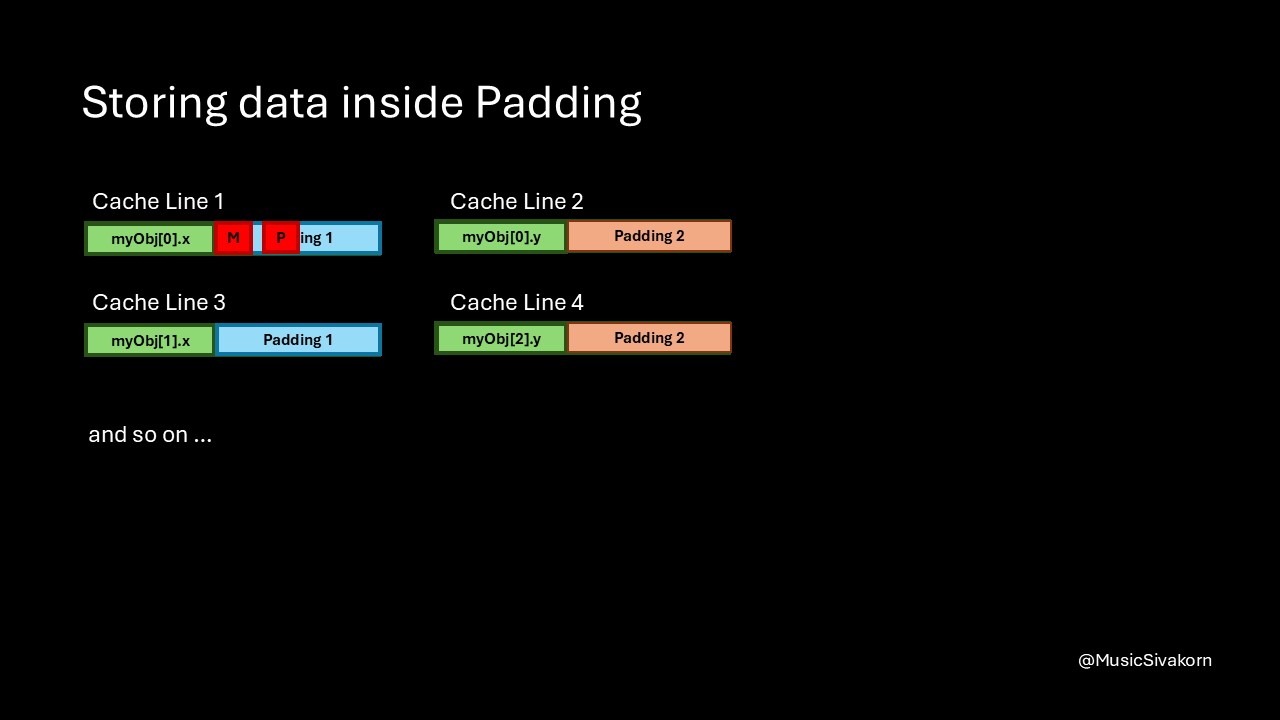

On a first glance, you may think that this problem is easy to solve by storing some data inside this padding space. But doing this may accidentally introduce another false sharing for another set of data.

The variable M and P are stored in the padding area. False Sharing can occur if one core modifies the variable M, and another modifies the variable P.

The variable M and P are stored in the padding area. False Sharing can occur if one core modifies the variable M, and another modifies the variable P.

So, I would say that this is a trade-off. You eliminate a false sharing, but you must trade with some amount of space. In fact, you may store read-only data or data that is not going to be frequently updated inside this padding, but you must know what you are doing.

Finally, this is the end of this part. This part is the final part of the cache coherence series. There might be some more extra parts supporting content of this series, such as a more in-depth explanation of spatial locality and how alignas(N) works. Let’s see what they will be.

If you enjoy this blog, you can support me with a cup of coffee. Thank you for reading until here and see you then!

This blog is originally published in Medium.