Cache Coherency Series: Part 2 — Cache Coherence Protocol

Published:

Let’s review a bit what we covered in the previous part. We talked about

- How a core retrieves data from RAM.

- The problem occurs in multicore programming.

- A mechanism, cache coherency, to solve the problem.

- Question about inefficiency of this mechanism

Here is a recap on how the cache coherency works.

Recap on how cache coherency from the previous part works. It is unoptimized yet.

Recap on how cache coherency from the previous part works. It is unoptimized yet.

In this part, we will re-explain the cache coherence mechanism from the previous part in a more formal way and use it to address the question about how to optimize the mechanism.

To formalize the mechanism, we need to define states, which tell the status of each cache line. We will start from having three states.

- M (Modified): The core with State M has modified data in a cache line. Only this core has an updated cache line.

- S (Shared): This core has an unmodified cache line in a read-only permission. The other cores can have the same cache line as well.

- I (Invalid): The cache line of this core is invalid. If the core reads this cache line, the cache miss occurs.

Then, we need to define what each core can do. So, we need to define CPU operations.

- CPURead: The core wants to read the data.

- CPUWrite: The core wants to write the data.

When each core wants to do an operation, it has to send a signal to the bus. CPURead and CPUWrite only tells the intention of the core, but we have to tell the other cores what to do when a particular core wants to do something. As a result, the core has to send a signal to the bus, and we have to define it.

- BusRTS (Bus ReadToShare): There is a core that wants to read data.

- BusRTW (Bus ReadToWrite): There is a core that wants to read data with the intention to modify the read data.

- BusINV (Bus Invalidation): There is a core that wants the other cores to invalidate their own cache line.

- BusWB (Bus WriteBack): The core, currently holding a modified cache line, writes its updated data back to main memory.

SIDE NOTE: For each cache line, apart from data, it also contains additional metadata bits, which are used to manage its state and identity. The examples of metadata bits are

- Tag bits, which are used to identify the cache line in the cache,

- State bits, which are used to define the current coherence state of the cache line

- Valid bit, which is used to indicate of the cache line contains valid data.

I will not go into detail as it is not necessary to understand the rest of the content in this part, but you can read more from here if you want to know more how the cache architecture really is.

Now, it’s time to re-explain the mechanism to be more precise by using these tools.

Initially, each core does not have a cache line. Then, all three cores receive CPURead to read variable x. All cores then send BusRTS to the bus. The cache line containing the variable x is fetched from RAM and sent to all cores. Now, the cache line in each core has a State S.

Each core receiving CPURead sends BusRTS to the bus to fetch the cache line from RAM.

Each core receiving CPURead sends BusRTS to the bus to fetch the cache line from RAM.

Then, the second core wants to update the variable x to be 42. It receives CPUWrite to write update the variable x.

The second core, currently in State S, broadcasts BusRTW through the bus to the other cores. When the other cores see this signal for a cache line they hold in State S, they know their copy is about to become stale and immediately change their state to I to prevent inconsistency because their cache line is going to be stale now.

Once the bus transaction is complete, the second core upgrades its state from S to M and performs the write.

The second core updates the variable x.

The second core updates the variable x.

When the first core wants to read the variable x, it receives CPURead. It then broadcasts BusRTS. The second core snooping the bus notices the read request for the memory address that it holds in a modified state. It writes its updated cache line back to RAM first, and RAM then provides the updated cache line back to the first core.

Finally, the cache line’s state of the first and second core is S because its data is now consistent with RAM.

The first core then reads the updated data.

The first core then reads the updated data.

We finish it! We have re-explained the mechanism in more precise and formal way.

Now, it’s time for the question. Why is this mechanism slow?

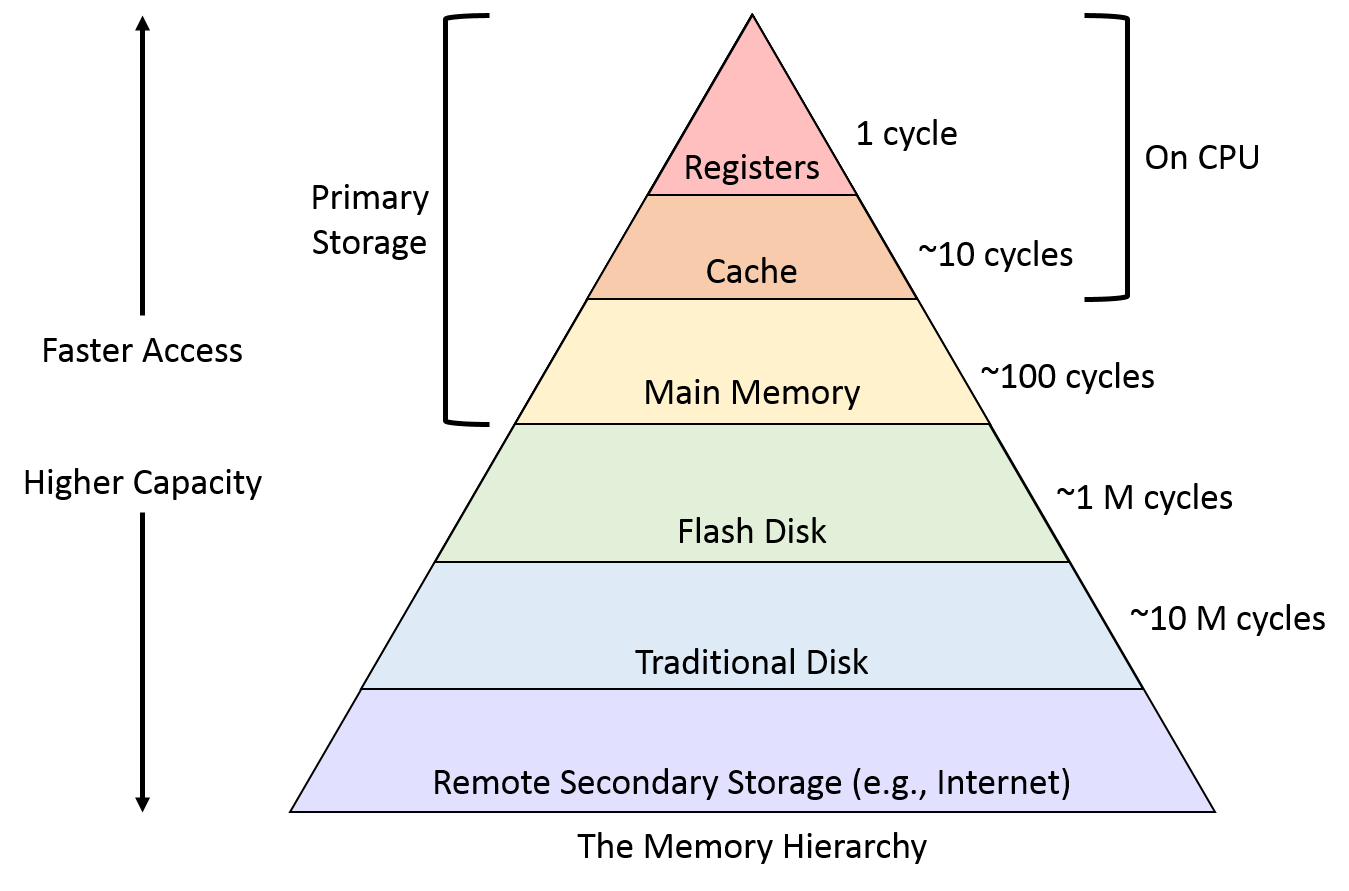

In memory hierarchy diagram, accessing cache is significantly faster than RAM. In other words, the number of cycles CPU uses to access the cache is significantly less than that of RAM.

The number of CPU cycles using to access each type of memory. You can notice that it is 10 times slower. Ref: Memory Hierarchy·GitBook

The number of CPU cycles using to access each type of memory. You can notice that it is 10 times slower. Ref: Memory Hierarchy·GitBook

In our mechanism, when another cache wants to get an updated cache line, the core updating the cache line has to write its cache line back to RAM first, and another core has to fetch it from RAM. The problem is that accessing RAM is extremely slow comparing to accessing the cache.

Accessing RAM is slow, and this mechanism accesses RAM two times.

Accessing RAM is slow, and this mechanism accesses RAM two times.

Because the second core already has an updated cache line, why don’t we let it share to other cores directly? This technique is called cache-to-cache transfer.

However, to do this, one more state must be defined.

- O (Owner): The core has modified data in a cache line. The other cores can also have this updated cache line as well.

Let me show first how to apply State O to the mechanism before explaining why it matters.

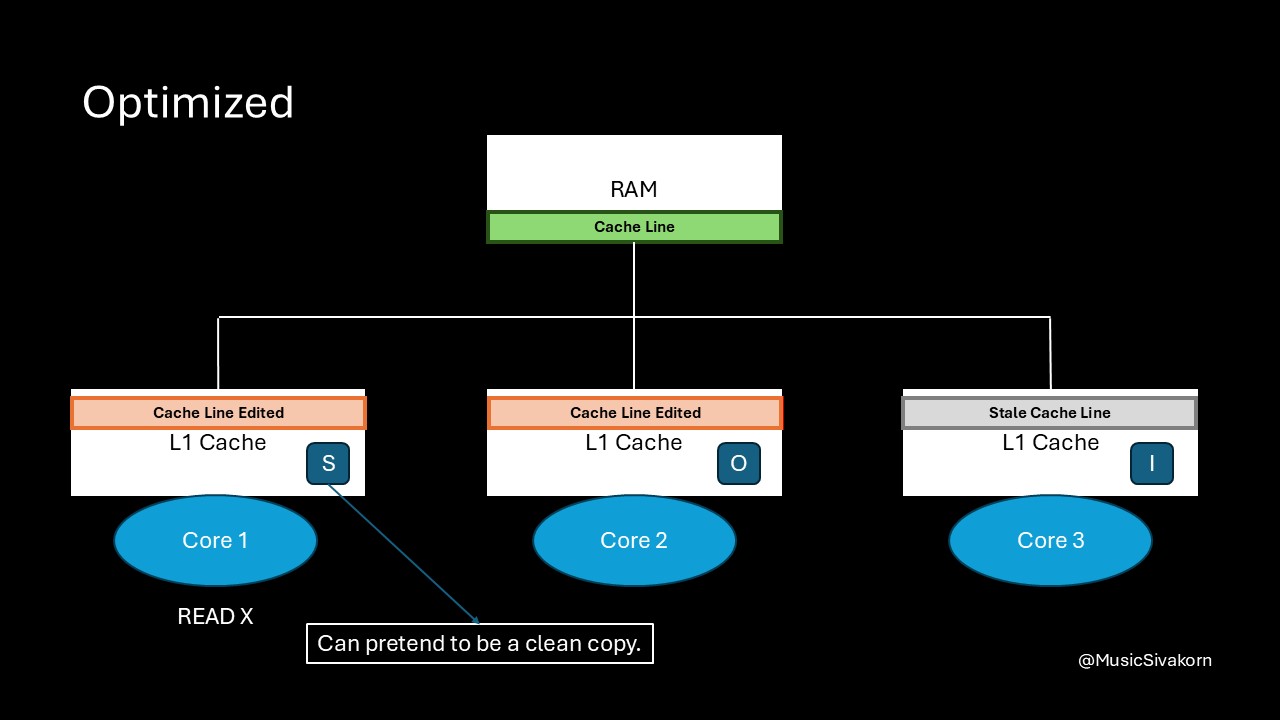

The first core wants to read the variable x, but it now has a stale cache line. So, it broadcasts BusRTS through the bus. Instead of updating RAM, the second core can directly provide the updated cache line to the first core.

The second core’s cache line changes its state to O. This matters to us, as a mechanism implementor, because we have to keep track who the owner of this updated cache line is.

The first core’s cache line state becomes S. It does not know who the provider is, and it does not matter in the view of the first core, and for us too, as opposed to the State O of the second core. It is enough to be certain that this is the most updated cache line to provide variable x. In other words, this cache line in the first core can pretend as if this cache line cleans.

Because of having State O, the second core does not need to immediately write the updated cache line back to RAM. It provides its update directly to other cores. As a result, this mechanism now becomes faster since it allows cache-to-cache transfer.

The first core reads the variable x, and the second core provides the cache line directly to the first core.

The first core reads the variable x, and the second core provides the cache line directly to the first core.

But now comes the problem again. Can you spot it?

We have made sure all the CPU cores can see the right data, but what about the rest of the system?

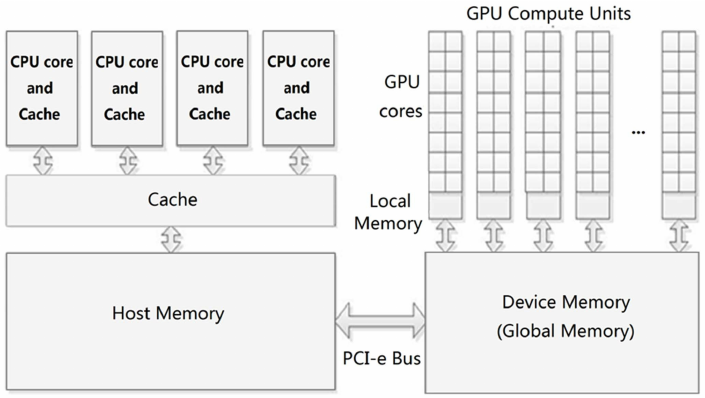

Consider a device like a GPU. It often needs to read data that the CPU has already prepared — for example, a texture, a list of vertices, or even a small variable that controls a rendering effect. For maximum performance, GPUs frequently access data directly from RAM using a technique called Direct Memory Access (DMA), which completely bypasses the CPU’s caches.

How GPU and CPU are connected together. Ref: here

How GPU and CPU are connected together. Ref: here

What happens if our beloved expensive GPU is instructed to read the value of variable x to perform a computation?

The GPU will initiate a DMA (Direct memory access) read from RAM. In our current mechanism, RAM still holds the old, stale value of x. The updated value, 42, only exists in the caches of the first and second core. The GPU would read the wrong data from RAM and proceed with an incorrect computation.

However, in this optimized mechanism, we have not determined when the updated data is going to be written back to RAM yet. We do not even have a CPU operation to instruct CPU to write data back to RAM.

So, let’s define one more CPU operation.

- CPURepl: The core wants to evict the current cache line.

When we need, we can instruct the second core with CPURepl to write the updated cache line back to RAM. Then, the second core’s cache line state changes to I since we design that CPURepl is the operation to evict the cache line. In fact, we can also design the operation so that it changes to state S instead. It depends on our design.

Finally, the result is that we don’t have to always write back the data. We can write it back when we only want.

We have done the optimization!

The second core writes data back to RAM.

The second core writes data back to RAM.

Until now, you may be overwhelmed by the content. It is almost the end of this part. Let me summarize what we have covered until here.

- In the previous part, the mechanism is slow because it accesses RAM a lot. The updated cache line is written back to RAM, and the other cores have to fetch it from RAM.

- We introduce 3 CPU states, which are M, S, and I.

- We introduce CPU operations (CPURead and CPUWrite) and bus transaction signals (BusRTS, BusRTW, BusINV, BusWB).

- We use it to re-explain the (unoptimized) mechanism.

- We revisit on why accessing RAM is slow once more.

- We introduce one more CPU state, which is O, and use it to create an optimized mechanism by using cache-to-cache transfer.

- We point out the problem that RAM is still not updated, and we do not have any way to update data back.

- We introduce one more CPU operation, CPURepl, and use it to solve this problem.

In fact, these mechanisms are already standardized as a protocol. The unoptimized mechanism is MSI protocol, and the optimized mechanism is MOSI protocol. You can read more details of these protocols in Wikipedia. Although it uses different notation from this blog, the concept is the same. I explain this mechanism using the same notations I have learned.

Before concluding this part, in fact, there are two types of cache coherence protocols.

- Snooping Protocols: This is the method we have done in the part 1 and 2. Each core (cache controller, to be more precise) monitors (snoops) the shared bus for memory transaction.

- Directory-Based Protocols: It has a directory, which can be either centralized or distributed depending on the design, to keep track of the sharing status of each cache line.

The protocol explained in this part is applied for only the snooping protocols. Directory-Based Protocols will be discussed later.

Now, let’s finish this part with another problem! Multicore programming has a lot of problems. The assumption of this problem is that the CPU will use the unoptimized mechanism (MSI protocol). The reason is that this problem is about latency, and I want to emphasize it.

Assuming that the current cache line of all cores has two variables, which are x and y. When the second core changes the value of variable y, the cache line in the other cores becomes stale. When the first core wants to read the variable x, the second core must update data in RAM, and the first core has to fetch the updated cache line from RAM.

What is the problem here?

In the next part, I will cover this “false sharing” problem. If you feel confused and overwhelmed by the content of this part, you can still follow my next part. I will not use and mention any state, CPU operations, and bus transaction to explain other further problems in the remaining parts.

The purpose of this part is only to introduce a formal and precise way to explain the cache coherence mechanism. However, we can still explain related problems without using this level of formality and precision!

However, the content in this part is still essential if you really want to deep dive into more advanced topics of computer architecture.

If you enjoy this blog, you can support me with a cup of coffee. Thank you for reading until here and see you then!

This blog is originally published in Medium.